The content displayed below is for educational and archival purposes only.

Unless stated otherwise, content is © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania

You may be able to find the original on wol.jw.org

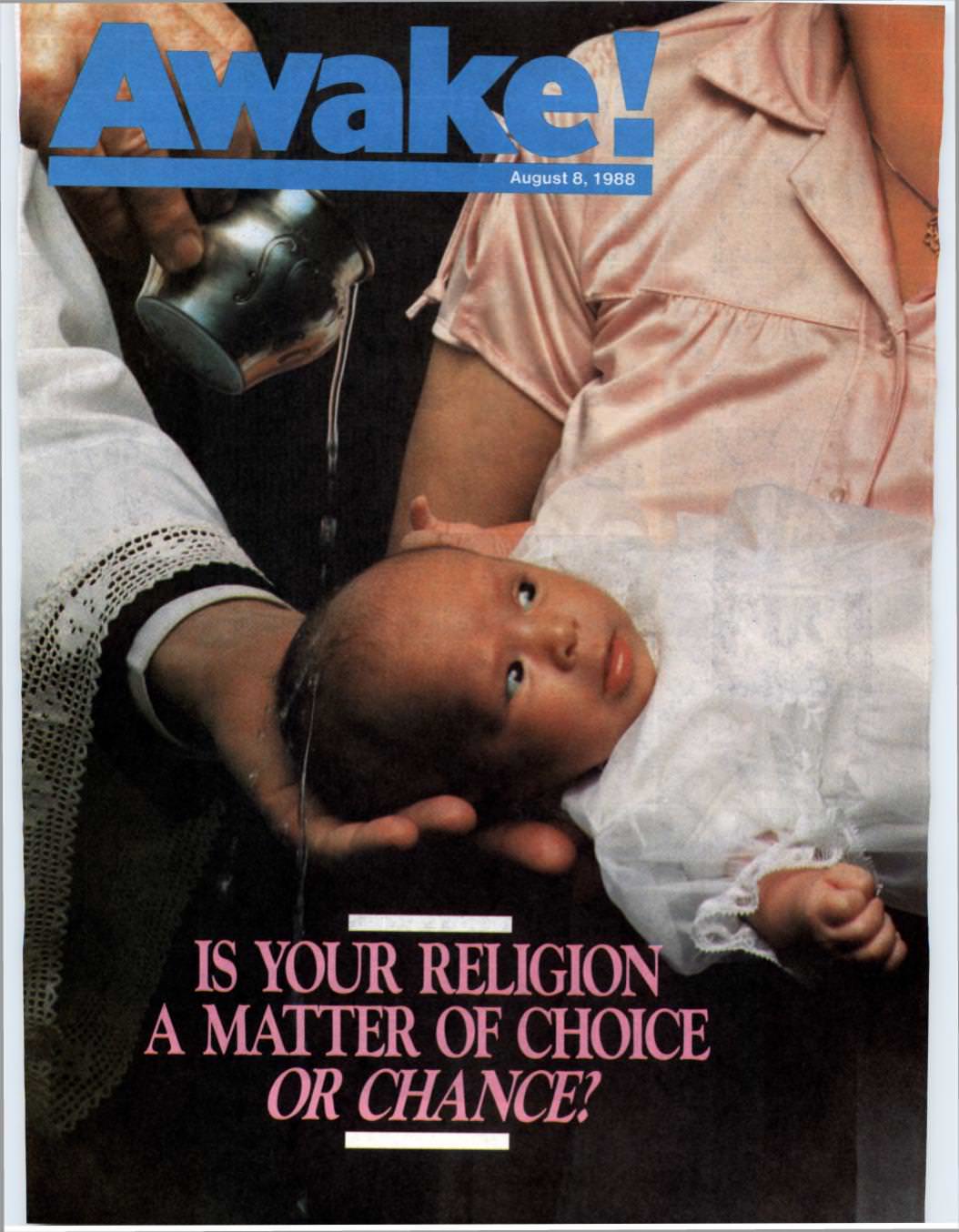

Should Your Birthplace Determine Your Religion?

THE way you speak and the way you eat; the way you dress and the way you sleep—all of that, and much more, may well depend on where you were born. Although we may be unaware of it, our roots affect us throughout our lives, molding our customs, our thinking, and our beliefs.

María, a Spaniard, is a Catholic because she was born in Catholic Spain. Martin is a Lutheran Protestant because he was born in Lübeck in northern Germany. Abdullam was born in West Beirut, so he is a Muslim.

Today, they, together with millions of others like them, adhere to their respective religions. The fact is that people often owe their religion to nothing more than geography and quirks of history. Unknown to them, their religion may have been decided by the whim of a political ruler centuries ago.

This was the case with Lisette, born in a village in the Federal Republic of Germany’s Black Forest. She was baptized as a Lutheran because for generations everybody in that part of her village was a loyal subject of the duke of Württemberg, a Protestant. Had she been born just a short distance down the road, she would have been a staunch Catholic because that part of the village was the domain of a Catholic ruler.

These artificial religious barriers date from the time of the Reformation in the 16th century. After a long and violent period of religious upheaval, it was agreed that each prince should determine the religion practiced in his domain. The argument was, Since men cannot agree, the monarch must decide.

Some unfortunate villagers found themselves on a religious merry-go-round as consecutive rulers changed religious horses. Other towns were arbitrarily divided on religion because the regional frontier happened to go through the town.

Not all rulers joined the Protestant bandwagon for pious reasons. Henry VIII of England, a former prominent defender of the Catholic faith, was annoyed when the pope refused to grant him a divorce from his first wife. His solution was simple. He broke with Rome and made himself the head of the Church of England, expecting his subjects to follow suit dutifully, which most of them eventually did.

Occasionally, whole countries were “converted” by missionaries who appeared close on the heels of foreign invaders. In Mexico the first Franciscan friars arrived a few years after the Spanish conquest. They claimed to have baptized more than five million natives in just 30 years, even though at first they did not speak the indigenous languages. This national conversion was described by one historian as “an extraordinary mixture of force, cruelty, stupidity and greed, redeemed by occasional flashes of imagination and charity.” Thus the European powers of the day cut up the world religiously as well as politically.

Centuries earlier the Muslim conquests of North Africa, the Middle East, and large areas of Asia led to the vast majority of the people in these lands becoming Muslims.

Today, the historical reasons for the religious divisions of mankind are largely forgotten; nevertheless, most people remain in the religion of their birthplace. But should the religion of our “choice” be left to chance? Should religion be a mere hand-me-down? Or should it result from a deliberate, rational decision? A look at Christianity in the first century will help to answer these questions.

Henry VIII decided the religion of millions