The content displayed below is for educational and archival purposes only.

Unless stated otherwise, content is © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania

You may be able to find the original on wol.jw.org

Gift of Life or Kiss of Death?

“How many people have to die? How many deaths do you need? Give us the threshold of death that you need in order to believe that this is happening.”

DON FRANCIS, an official of the CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control), pounded his fist on the table as he shouted the above words at a meeting with top representatives of the blood-banking industry. The CDC was trying to convince the blood bankers that AIDS was spreading through the nation’s blood supply.

The blood bankers were unconvinced. They called the evidence tenuous—just a handful of cases—and decided not to step up blood testing or screening. That was on January 4, 1983. Six months later, the president of the American Association of Blood Banks asserted: “There is little or no danger to the general public.”

For many experts, there was already enough evidence to warrant some action. And since then, that original “handful of cases” has ballooned alarmingly. Before 1985, perhaps 24,000 people were given transfusions tainted with HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), which causes AIDS.

Contaminated blood is an appallingly efficient way to spread the AIDS virus. According to The New England Journal of Medicine (December 14, 1989), a single unit of blood may carry enough virus to cause up to 1.75 million infections! The CDC told Awake! that by June 1990, in the United States alone, 3,506 people had already developed AIDS from blood transfusions, blood components, and tissue transplants.

But those are mere numbers. They can’t begin to convey the depth of the personal tragedies involved. Consider, for instance, the tragedy of Frances Borchelt, 71 years old. She adamantly told doctors that she did not want a blood transfusion. She was transfused anyway. She died agonizingly of AIDS as her family watched helplessly.

Or consider the tragedy of a 17-year-old girl who, suffering from heavy menstrual bleeding, was given two units of blood just to correct her anemia. When she was 19 years old and pregnant, she found out that the transfusion had given her the AIDS virus. At 22 she came down with AIDS. Besides learning that she would soon die of AIDS, she was left wondering if she had passed the disease on to her baby. The list of tragedies goes on and on, ranging from babies to the elderly, all over the world.

In 1987 the book Autologous and Directed Blood Programs lamented: “Almost as soon as the original risk groups were defined, the unthinkable occurred: the demonstration that this potentially lethal disease [AIDS] could and was being transmitted by the volunteer blood supply. This was the most bitter of all medical ironies; that the precious life-giving gift of blood could turn out to be an instrument of death.”

Even medicines derived from plasma helped to spread this plague around the world. Hemophiliacs, most of whom use a plasma-based clotting agent to treat their illness, were decimated. In the United States, between 60 and 90 percent of them got AIDS before a procedure was set up to heat-treat the medicine in order to rid it of HIV.

Still, to this day, blood is not safe from AIDS. And AIDS is not the only danger from blood transfusion. Far from it.

The Risks That Dwarf AIDS

“It is the most dangerous substance we use in medicine,” Dr. Charles Huggins says of blood. He should know; he is the director of the blood transfusion service at a Massachusetts hospital. Many think that a blood transfusion is as simple as finding someone with a matching blood type. But besides the ABO types and the Rh factor for which blood is routinely cross-matched, there may be 400 or so other differences for which it is not. As cardiovascular surgeon Denton Cooley notes: “A blood transfusion is an organ transplant. . . . I think that there are certain incompatibilities in almost all blood transfusions.”

It is not surprising that transfusing such a complex substance might, as one surgeon put it, “confuse” the body’s immune system. In fact, a blood transfusion can suppress immunity for as long as a year. To some, this is the most threatening aspect of transfusions.

Then there are infectious diseases as well. They have exotic names, such as Chagas’ disease and cytomegalovirus. Effects range from fever and chills to death. Dr. Joseph Feldschuh of the Cornell University of Medicine says that there is 1 chance in 10 of getting some sort of infection from a transfusion. It is like playing Russian roulette with a ten-chamber revolver. Recent studies have also shown that blood transfusions during cancer surgery may actually increase the risk of recurrence of the cancer.

No wonder a television news program claimed that a blood transfusion could be the biggest obstacle to recovery from surgery. Hepatitis infects hundreds of thousands and kills many more transfusion recipients than AIDS does, but it gets little of the publicity. No one knows the extent of the deaths, but economist Ross Eckert says that it may be the equivalent of a DC-10 airliner full of people crashing every month.

Risk and the Blood Banks

How have blood banks responded to the exposure of all these risks in their product? Not well, the critics charge. In 1988 the Report of the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic accused the industry of being “unnecessarily slow” in reacting to the AIDS threat. Blood banks had been urged to discourage members of high-risk groups from donating blood. They had been urged to test the blood itself, screening it for signs of coming from high-risk donors. The blood banks delayed. They pooh-poohed the risks as so much hysteria. Why?

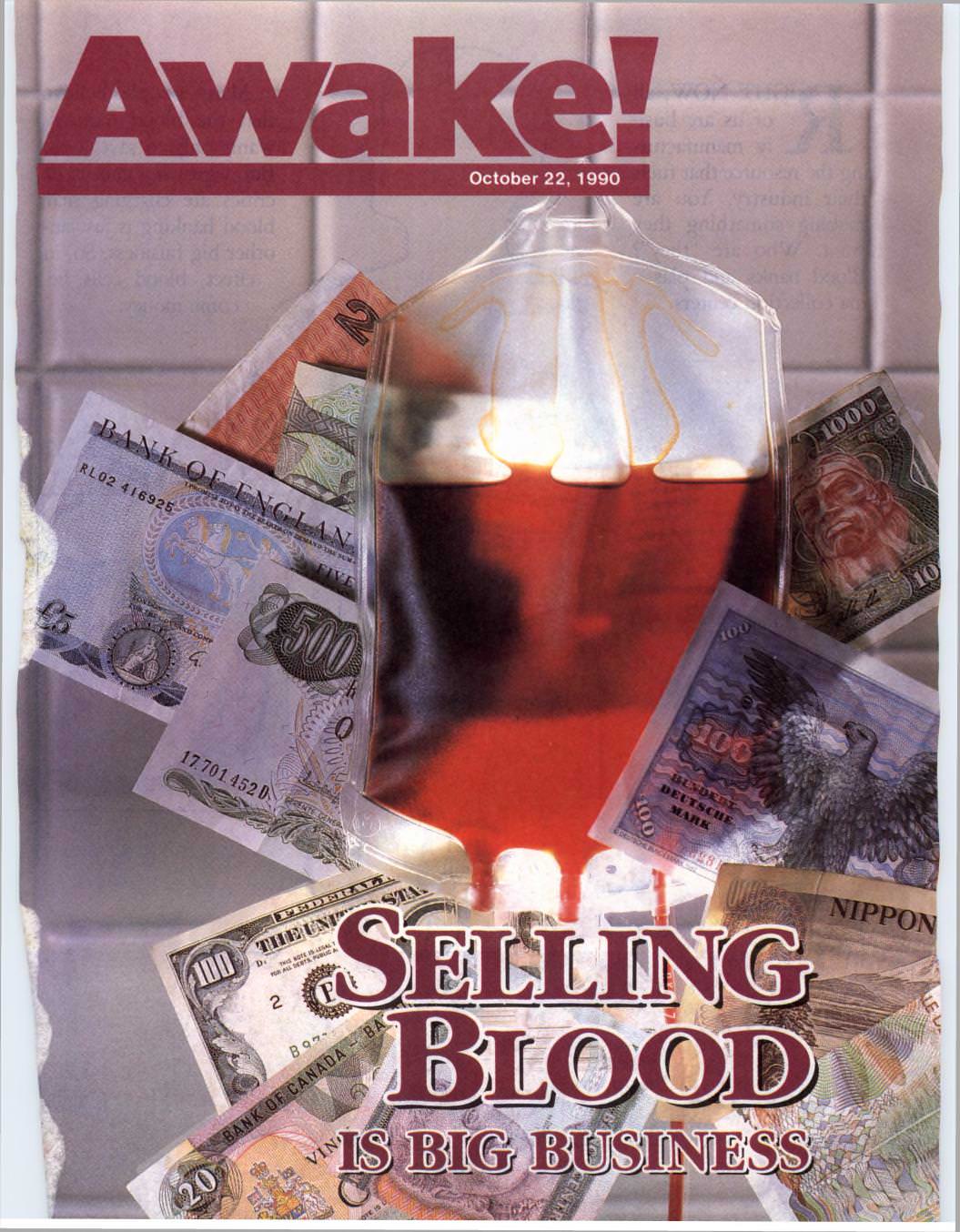

In his book And the Band Played On, Randy Shilts charges that some blood bankers opposed further testing “almost solely on fiscal grounds. Although largely run by non-profit organizations like the Red Cross, the blood industry represented big money, with annual receipts of a billion [a thousand million] dollars. Their business of providing the blood for 3.5 million transfusions a year was threatened.”

Furthermore, since nonprofit blood banks depend so heavily on volunteer donors, they hesitated to offend any of them by excluding certain high-risk groups, homosexuals in particular. Gay-rights advocates warned darkly that forbidding them to donate blood would violate their civil rights and would smack of the concentration-camp mentality of another era.

Losing donors and adding new tests would also cost more money. In the spring of 1983, the Stanford University Blood Bank became the first to use a surrogate test on blood, which could indicate whether the blood came from donors at high risk for AIDS. Other blood bankers criticized the move as a commercial ploy to attract more patients. Tests do increase prices. But as one couple, whose baby was transfused without their knowledge, put it: “We certainly would have paid an additional $5 a pint” for such tests. Their baby died of AIDS.

The Self-Preservation Factor

Some experts say that the blood banks are sluggish to respond to dangers in blood because they do not have to answer for the consequences of their own failures. For instance, according to the report in The Philadelphia Inquirer, the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) is responsible for seeing that the blood banks are up to standard, but it relies heavily on the blood banks to set those standards. And some of the officials of the FDA are former leaders in the blood industry. Thus, inspections of blood banks actually decreased in frequency as the AIDS crisis unfolded!

U.S. blood banks have also lobbied for legislation that protects them from lawsuits. In almost every state, the law now says that blood is a service, not a product. That means that a person suing a blood bank must prove negligence on the bank’s part—a tough legal obstacle. Such laws may make blood banks safer from lawsuits, but they do not make blood safer for patients.

As economist Ross Eckert reasons, if the blood banks were held liable for the blood they traffic in, they would do more to ensure its quality. Retired blood banker Aaron Kellner agrees: “By a bit of legal alchemy, blood became a service. Everybody was home free, everybody that is, except the innocent victim, the patient.” He adds: “We could at least have pointed out the inequity, but we did not. We were concerned with our own peril; where was our concern for the patient?”

The conclusion seems inescapable. The blood-banking industry is far more interested in protecting itself financially than it is in protecting people from the hazards of its product. ‘But do all these hazards really matter,’ some might reason, ‘if blood is the only possible treatment to save a life? Don’t the benefits outweigh the risks?’ These are good questions. Just how necessary are all those transfusions?

[Blurb on page 9]

Doctors go to great lengths to protect themselves from their patients’ blood. But are patients sufficiently protected from transfused blood?

[Box/Picture on page 8, 9]

Is Blood Safe From AIDS Today?

“IT’S Bloody Good News,” proclaimed a headline in the New York Daily News on October 5, 1989. The article reported that the chances of getting AIDS from a blood transfusion are 1 in 28,000. The process for keeping the virus out of the blood supply, it said, is now 99.9 percent effective.

Similar optimism reigns in the blood-banking industry. ‘The blood supply is safer than ever,’ they claim. The president of the American Association of Blood Banks said that the risk of acquiring AIDS from blood had been “virtually eliminated.” But if blood is safe, why have both courts and doctors slapped it with such labels as “toxic” and “unavoidably unsafe”? Why do some doctors operate wearing what look like space suits, replete with face masks and wading boots, all to avoid contact with blood? Why do so many hospitals ask patients to sign a consent form relieving the hospital of liability for the harmful effects of blood transfusions? Is blood really safe from diseases such as AIDS?

The safety depends on the two measures used to protect blood: screening the donors who supply it and testing the blood itself. Recent studies have shown that in spite of all the efforts to screen out blood donors whose life-style puts them at high risk for AIDS, there are still some who slip through the screen. They give wrong answers to the questionnaire and donate blood. Some just want to find out discreetly if they are infected themselves.

In 1985 blood banks began to test blood for the presence of the antibodies that the body produces to fight the AIDS virus. The problem with the test is that a person can be infected with the AIDS virus for some time before developing any antibodies that the test would detect. This crucial gap is called the window period.

The idea that there is 1 chance in 28,000 of getting AIDS from a blood transfusion comes from a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine. That periodical set the most likely window period at an average of eight weeks. Just months before, though, in June 1989, the same journal published a study concluding that the window period can be much longer—three years or more. This earlier study suggested that such long window periods may be more common than once thought, and it speculated that, worse, some infected people may never develop antibodies for the virus! The more optimistic study, however, did not incorporate these findings, calling them “not well understood.”

No wonder Dr. Cory SerVass of the Presidential Commission on AIDS said: “Blood banks can keep telling the public that the blood supply is as safe as it can be, but the public isn’t buying that anymore because they sense it isn’t true.”

[Credit Line]

CDC, Atlanta, Ga.

[Box on page 11]

Transfused Blood and Cancer

Scientists are learning that transfused blood can suppress the immune system and that suppressed immunity may adversely affect the survival rate of those operated on for cancer. In its February 15, 1987, issue, the journal Cancer reports on an informative study done in the Netherlands. “In the patients with colon cancer,” the journal said, “a significant adverse effect of transfusion on long-term survival was seen. In this group there was a cumulative 5-year overall survival of 48% for the transfused and 74% for the nontransfused patients.”

Physicians at the University of Southern California also found that of patients who had cancer surgery many more have a recurrence of cancer if they received a transfusion. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, March 1989, reported on a follow-up study of a hundred patients by these physicians: “The recurrence rate for all cancers of the larynx was 14% for those who did not receive blood and 65% for those who did. For cancer of the oral cavity, pharynx, and nose or sinus, the recurrence rate was 31% without transfusions and 71% with transfusions.”

In his article “Blood Transfusions and Surgery for Cancer,” Dr. John S. Spratt concluded: “The cancer surgeon may need to become a bloodless surgeon.”—The American Journal of Surgery, September 1986.

[Pictures on page 10]

That blood is a lifesaving medicine is debatable but that it kills people is not