The content displayed below is for educational and archival purposes only.

Unless stated otherwise, content is © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania

You may be able to find the original on wol.jw.org

A World Without Automobiles?

CAN you imagine a world without motor vehicles? Or can you name an invention that over the past century has changed the life-styles and behavior of people as fundamentally as they have? Without automobiles, there would be no motels, no drive-in restaurants, and no drive-in theaters. More important, without buses, taxis, cars, or trucks, how would you get to work? to school? How would farmers and manufacturers get their wares to market?

“One of every six U.S. businesses is dependent on the manufacture, distribution, servicing, or use of motor vehicles,” notes The New Encyclopædia Britannica, adding: “Sales and receipts of automotive firms represent more than one-fifth of the country’s wholesale business and more than one-fourth of its retail trade. For other countries these proportions are somewhat smaller, but Japan and the countries of western Europe have been rapidly approaching the U.S. level.”

Nevertheless, some people say a world without motor vehicles would be a better place. This they say for basically two reasons.

Worldwide Gridlock

If you have ever circled endlessly looking for a parking space, you need no one to tell you that even if cars are good, having too many in a crowded area is not. Or if you have ever been caught in a horrendous traffic jam, you know how frustrating it is to be trapped in a vehicle that is designed to move but that has been forced to a standstill.

In 1950, the United States was alone in having 1 car for every 4 persons. By 1974, Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Sweden had caught up. But by then the U.S. figure had risen to almost 1 car for every 2 persons. Now Germany and Luxembourg have about 1 motor vehicle for every 2 inhabitants. Belgium, France, Great Britain, Italy, and the Netherlands are not far behind.

Most large cities—no matter where they may be in the world—are degenerating into giant parking lots. For example, in India at the time of independence in 1947, New Delhi, its capital, boasted 11,000 cars and trucks. By 1993 the figure exceeded 2,200,000! An astronomical increase—but “a number that is expected to double by the end of the century,” according to Time magazine.

Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe, with only one fourth as many autos per capita as Western Europe, there are some 400 million potential customers. Within a few years, the situation in China, until now known for its 400 million bicycles, will have changed. As reported in 1994, “the government is laying plans for a rapid increase in auto production,” going from an annual 1.3 million cars to 3 million by the end of the century.

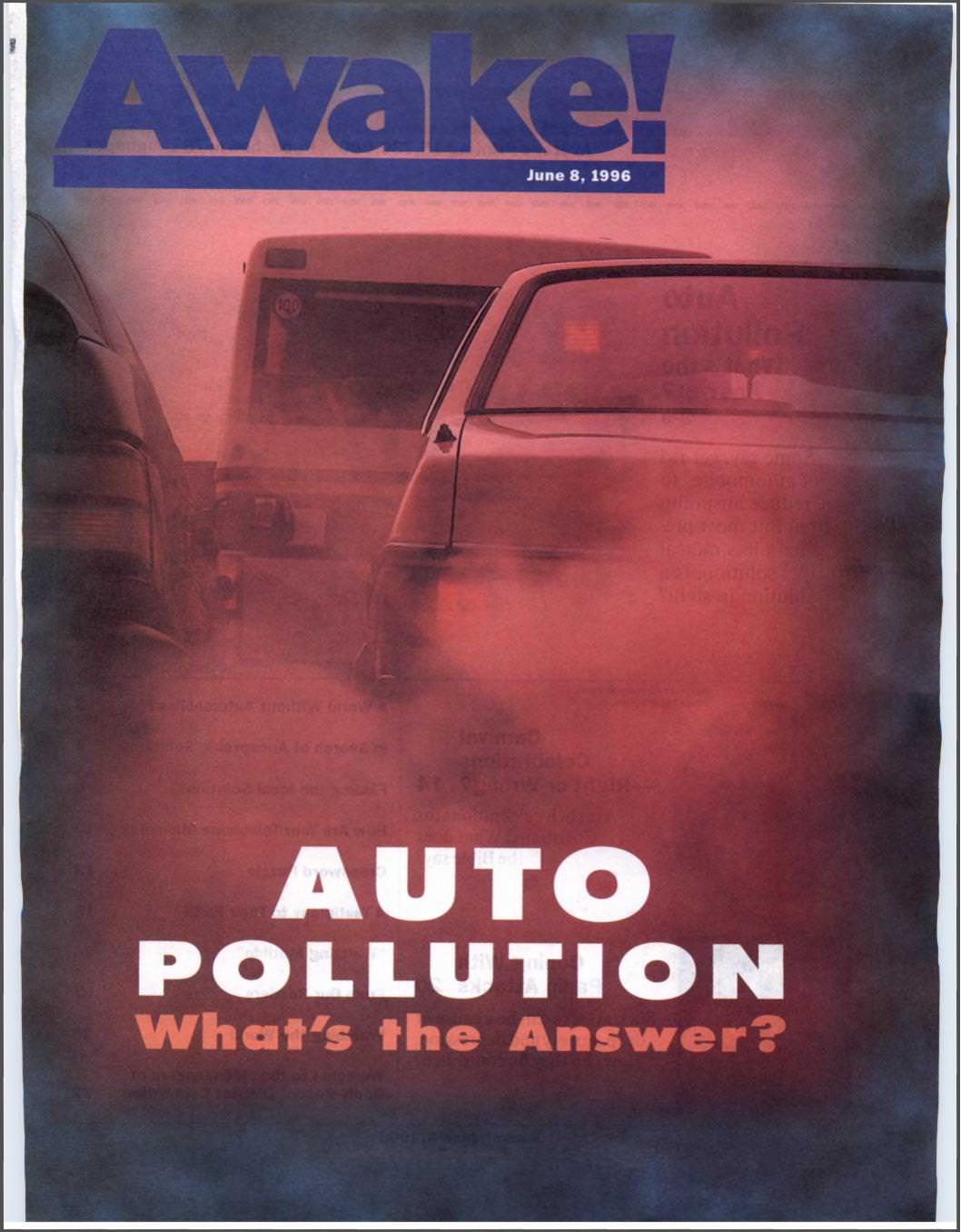

The Pollution Threat

“Britain has run out of fresh air,” said The Daily Telegraph of October 28, 1994. This is perhaps exaggerated but nevertheless true enough to cause concern. Professor Stuart Penkett, of the University of East Anglia, warned: “Motor cars are changing the chemistry of the whole of our background atmosphere.”

A high concentration of carbon monoxide pollution, says the book 5000 Days to Save the Planet, “deprives the body of oxygen, impairs perception and thinking, slows reflexes and causes drowsiness.” And the World Health Organization says: “Around a half of all city dwellers in Europe and North America are exposed to unacceptably high levels of carbon monoxide.”

It is estimated that in some places automobile emissions annually kill many people—in addition to causing billions of dollars in environmental damage. In July 1995 a television news report said that some 11,000 Britons die annually from car-induced air pollution.

In 1995 the United Nations Climate Conference was held in Berlin. Representatives from 116 countries agreed that something needed to be done. But to the disappointment of many, the task of adopting specific targets and setting down definite rules or of outlining precise programs was postponed.

In the light of what the book 5000 Days to Save the Planet said back in 1990, this lack of progress was probably to be expected. “The nature of political and economic power in modern industrial society,” it pointed out, “dictates that measures to combat environmental destruction are only acceptable if they do not interfere with the workings of the economy.”

Thus, Time recently warned of “the possibility that the buildup of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will gradually warm the globe. The result, according to many scientists, could be droughts, melting ice caps, rising sea levels, coastal flooding, more severe storms and other climatic calamities.”

The seriousness of the pollution problem demands that something be done. But what?