The content displayed below is for educational and archival purposes only.

Unless stated otherwise, content is © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania

You may be able to find the original on wol.jw.org

Insect-Borne Disease

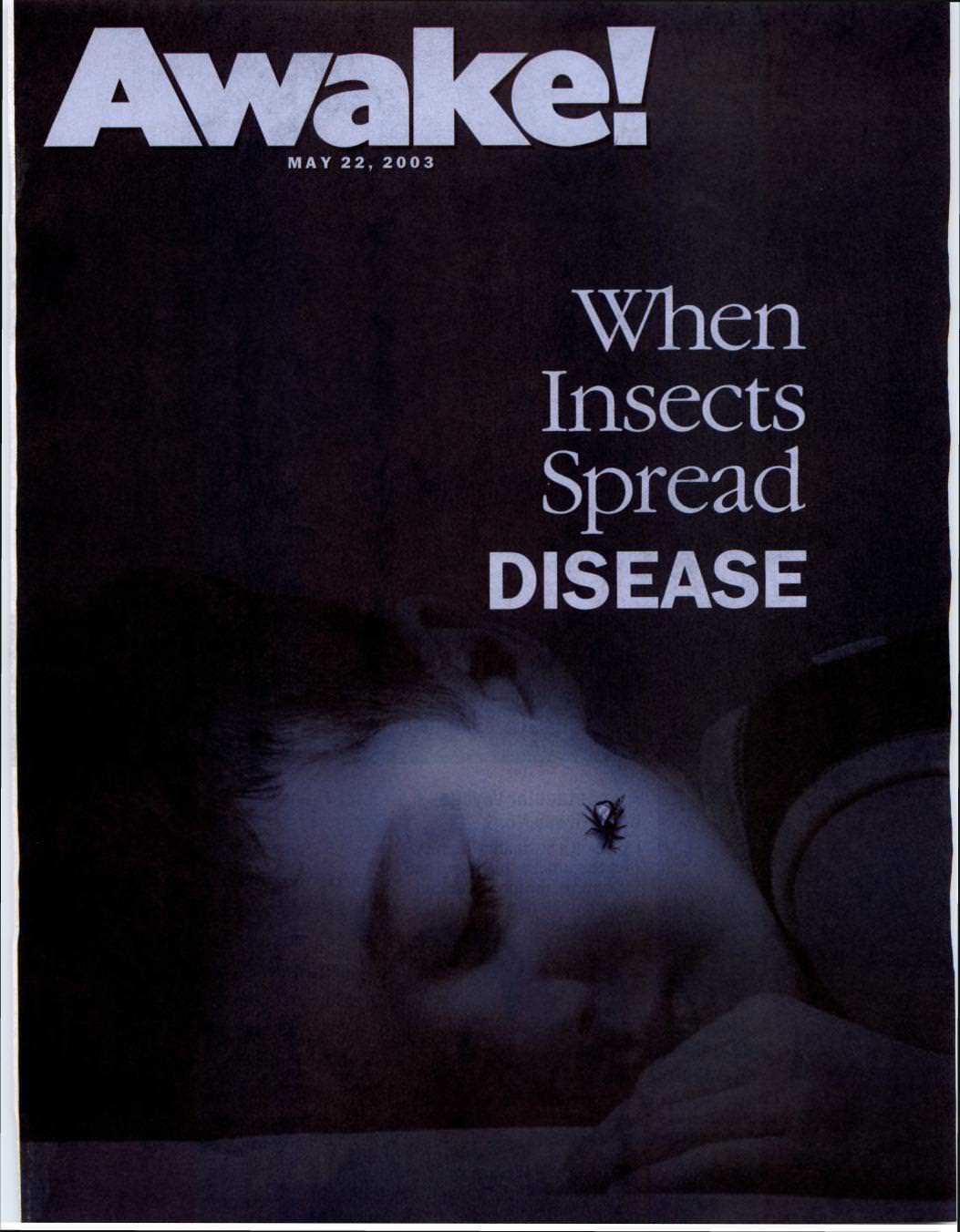

IT IS BEDTIME in a Latin-American home. A mother lovingly tucks her young son in and bids him good night. But in the dark a sleek, black kissing bug, less than an inch [less than 3 cm] long, slips out of a crevice in the ceiling over the bed. It drops undetected onto the sleeping child’s face and almost imperceptibly pierces the soft skin with its beak. As the bug gorges itself on blood, it also discharges its parasite-laden waste. Without waking, the boy scratches his face, rubbing the infected feces into the wound.

As a result of this one encounter, the child contracts Chagas’ disease. Within a week or two, he gets a high fever and his body swells. If he survives, the parasites may take up residence in his system, invading his heart, nerves, and internal tissues. As many as 10 to 20 years may pass without symptoms. But then he may develop lesions in his digestive tract, experience cerebral infection, and ultimately die of heart failure.

This fictionalized account realistically depicts how Chagas’ disease can be contracted. In Latin America, millions may be at risk of receiving this kiss of death.

Man’s Multilegged Companions

“Most of the major fevers of man are produced by micro-organisms that are conveyed by insects,” states the Encyclopædia Britannica. People commonly use the term “insect” to include not only true insects

The vast majority of insects are harmless to man, and some are very beneficial. Without them, many of the plants and trees that people and animals depend on for food would not be pollinated or bear fruit. Some insects help to recycle waste. Many insects feed exclusively on plants, while certain ones eat other insects.

Of course, there are insects that annoy man and beast with their painful bite or simply by their presence in vast numbers. Some also wreak havoc on crops. Worse, however, are insects that spread sickness and death. Insect-borne diseases “were responsible for more human disease and death in the 17th through the early 20th centuries than all other causes combined,” states Duane Gubler of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Presently, about 1 out of every 6 people is infected with a disease acquired through insects. Besides causing human suffering, insect-borne disease imposes a heavy financial burden, especially on developing countries

How Insects Make Us Sick

There are two main ways that insects serve as vectors

Cockroaches, which thrive in filth, are also suspected of mechanically transmitting disease. In addition, experts link a recent steep rise in asthma, especially among children, to cockroach allergies. For instance, picture Ashley, a 15-year-old girl who has spent many nights struggling to breathe because of her asthma. As her doctor is about to listen to her lungs, a cockroach falls out of Ashley’s shirt and runs across the examination table.

Diseases on the Inside

When insects harbor viruses, bacteria, or parasites inside their bodies, they can spread disease a second way

Still, other mosquitoes transmit a host of different maladies. WHO reports: “Of all disease-transmitting insects, the mosquito is the greatest menace, spreading malaria, dengue and yellow fever, which together are responsible for several million deaths and hundreds of millions of cases every year.” At least 40 percent of earth’s population are at risk for malaria, and about 40 percent for dengue. In many places, a person can contract both.

Of course, mosquitoes are not the only insects that carry disease inside them. Tsetse flies transmit the protozoa that cause sleeping sickness, afflicting hundreds of thousands of people and forcing whole communities to abandon their fertile fields. By transmitting the organism causing river blindness, blackflies have robbed some 400,000 Africans of sight. Sand flies can carry the protozoa that cause leishmaniasis, a group of disabling, disfiguring, and often fatal diseases that presently afflict millions of people of all ages around the world. The ubiquitous flea can host tapeworms, encephalitis, tularemia, and even plague

Lice, mites, and ticks can convey various forms of typhus, besides other diseases. Ticks in temperate lands around the world can carry potentially debilitating Lyme disease

A “Vacation” From Disease

It was only as recently as 1877 that insects were scientifically shown to transmit disease. Since then, massive campaigns to control or eliminate disease-carrying insects have been carried out. In 1939 the insecticide DDT was added to the arsenal, and by the 1960’s insect-borne disease was no longer regarded as a major threat to public health outside Africa. Emphasis shifted away from controlling the vectors to treating emergency cases with drugs, and interest in studying insects and their habitats waned. New medicines were also being discovered, and it seemed that science could find a “magic bullet” to deal with any illness. The world was enjoying a “vacation” from infectious disease. But the vacation was to end. The following article will discuss why.

[Blurb on page 3]

Today 1 person in 6 is infected with an insect-borne disease

[Picture on page 3]

The kissing bug

[Picture on page 4]

Houseflies carry disease-causing agents on their feet

[Pictures on page 5]

Many insects carry diseases inside their bodies

Blackflies carry river blindness

Mosquitoes carry malaria, dengue, and yellow fever

Lice can convey typhus

Fleas host encephalitis and other diseases

Tsetse flies transmit sleeping sickness

[Credit Lines]

WHO/TDR/LSTM

CDC/James D. Gathany

CDC/Dr. Dennis D. Juranek

CDC/Janice Carr

WHO/TDR/Fisher

[Picture Credit Line on page 4]

Clemson University - USDA Cooperative Extension Slide Series, www.insectimages.org