The content displayed below is for educational and archival purposes only.

Unless stated otherwise, content is © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania

You may be able to find the original on wol.jw.org

DID YOU KNOW?

In Bible times, how were scrolls made, and how were they used?

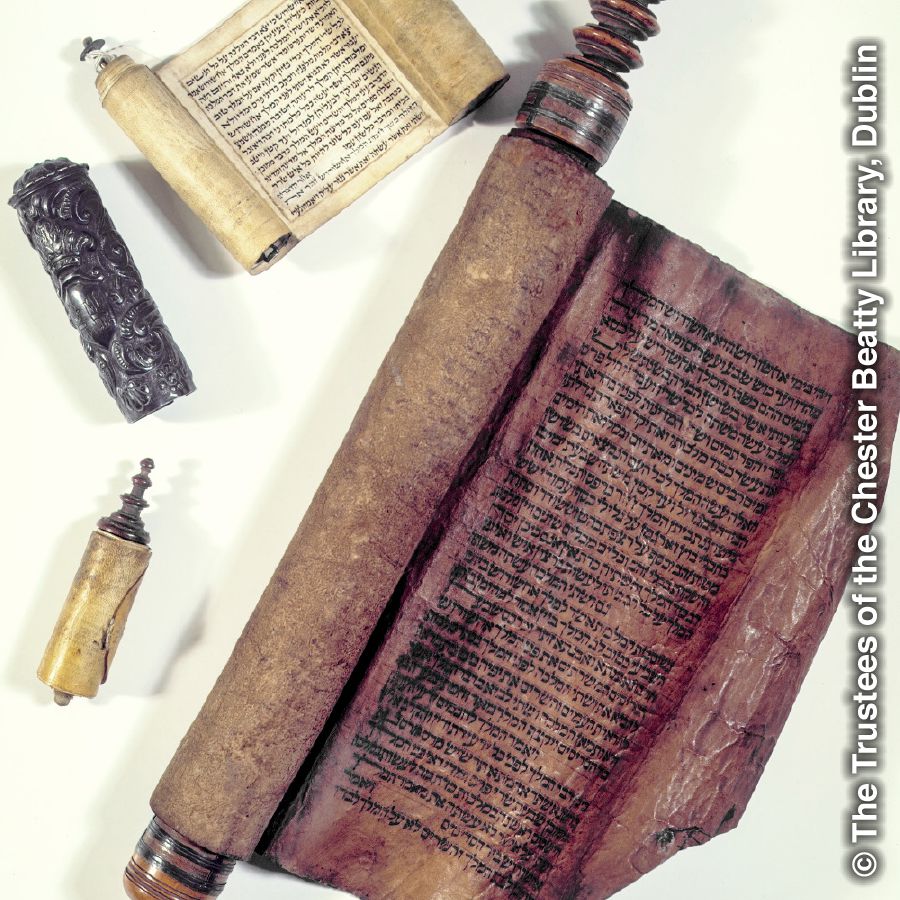

Later leather and vellum scrolls of the Bible book of Esther, from the 18th century C.E.

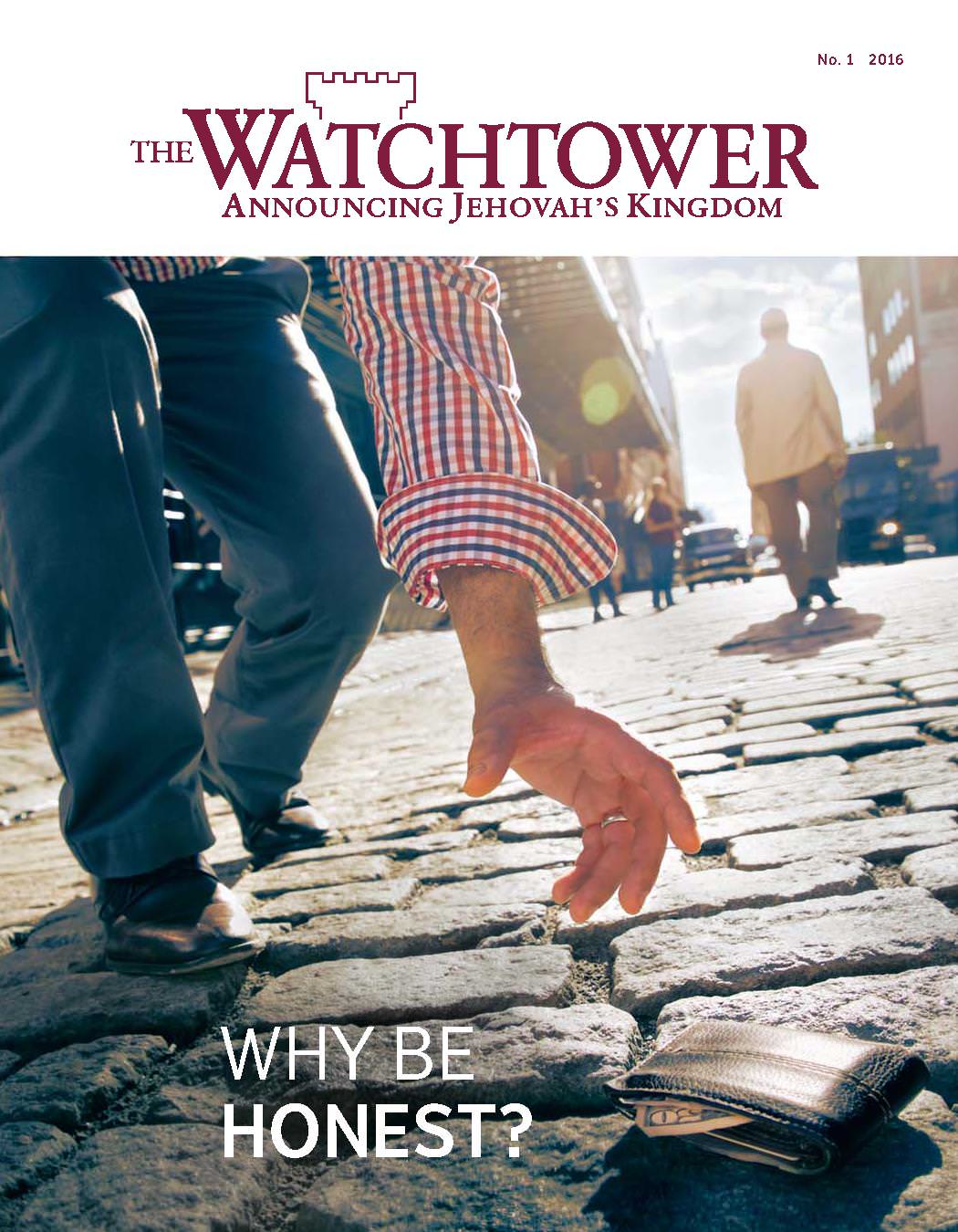

The Gospel of Luke speaks of Jesus’ opening the scroll of Isaiah, reading from it, and then rerolling it. At the end of John’s Gospel, John too spoke of a scroll, saying that he was not able to include in his scroll all the signs that Jesus had performed.

How were scrolls made? Pieces of such materials as leather, parchment, or papyrus were glued together to form a strip, or a roll. This could then be wrapped around a rod with the written face on the inside. The writing appeared in short vertical columns across the width of the roll. If the scroll was long, it would have rods at both ends, which the reader would use to unroll the text with one hand and roll it up with the other, until the desired place was found.

“A scroll had the advantage of being long enough [often about 33 feet (10 m)] to contain a whole book in a small volume, once it was rolled up,” says The Anchor Bible Dictionary. It is estimated that the Gospel of Luke, for example, would have required a roll some 31 feet (9.5 m) in length. In some cases, a scroll’s top and bottom edges were trimmed, rubbed smooth with pumice stone, and dyed.

Who may have been the “chief priests” who were mentioned in the Christian Greek Scriptures?

From the inception of the Israelite priesthood, only one man at a time served in the capacity of high priest, which initially was a lifelong appointment. (Numbers 35:25) Aaron was the first to serve in this capacity. Subsequently, the honor generally passed from father to oldest son. (Exodus 29:9) Many of Aaron’s male descendants served as priests, but only relatively few as high priests.

When Israel came under foreign domination, non-Israelite rulers appointed and removed Jewish high priests at will. It appears, however, that new appointees were almost always chosen from a select number of privileged families, mostly from the line of Aaron. The expression “chief priests” evidently refers to principal members of the priesthood. The chief priests may have included the heads of the 24 divisions of the priesthood; prominent members of high-priestly families; and former high priests who had been deposed, such as Annas.